Filmmakers have had a long history of admitting inspiration from previous films, oftentimes going undetected by audiences at the time of release. Most famously, Quentin Tarantino ‘stole’ the dance at Jack Rabbit Slim’s in Pulp Fiction from Fellini’s 8 ½ (in addition to countless grindhouse/cult re-interpretations – see any interview with him for reference). Martin Scorsese is another champion of cinema history, you don’t have to look hard to find his infatuation with Powell & Pressburger, or how Truffaut’s Jules & Jim influenced the energy of Goodfellas.

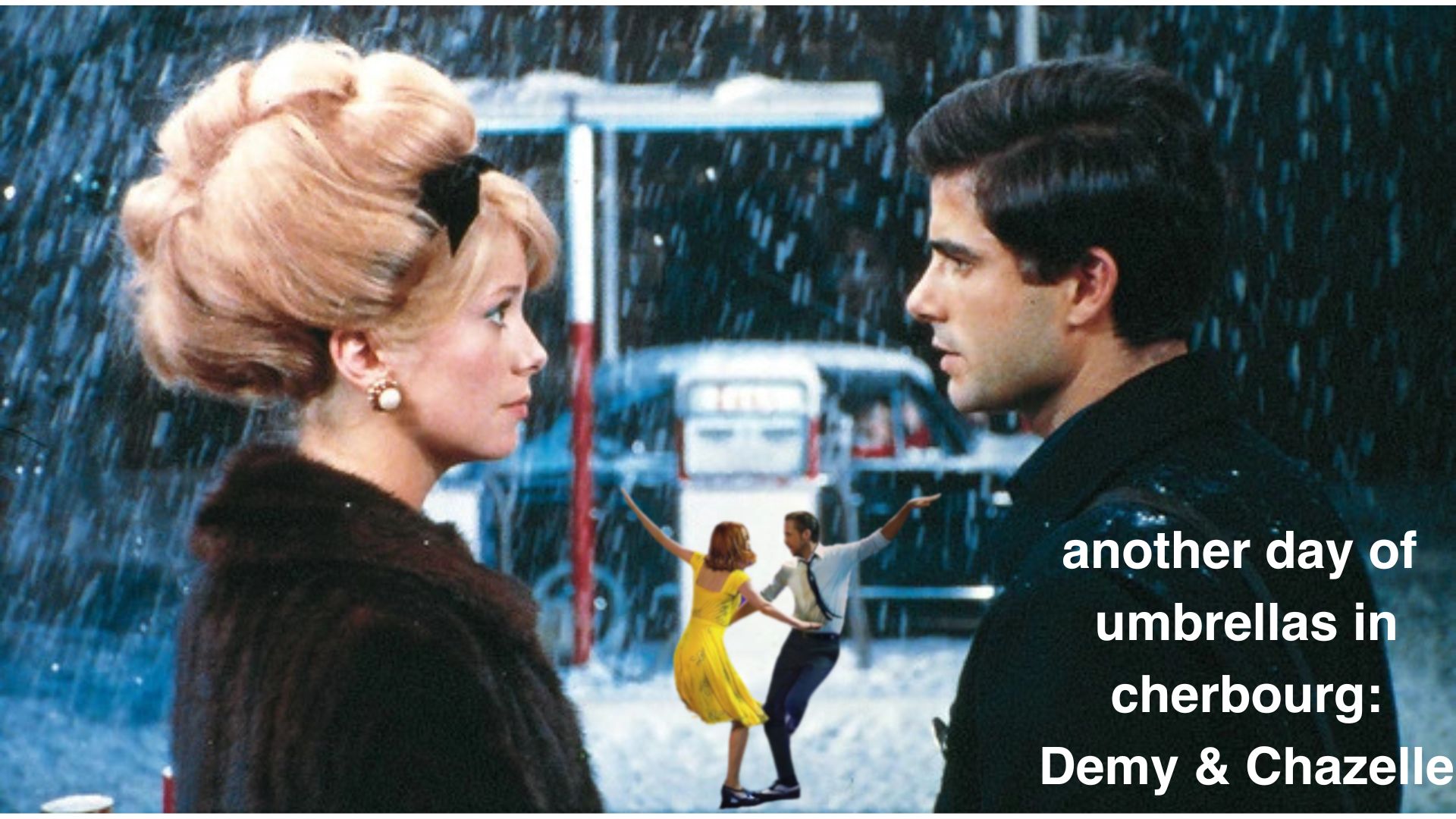

There are some, however, that are not as immediately recognizable. This is where I challenge any fans of Damien Chazelle’s La La Land, the near-best picture winner at the Oscars of 2017, to come see the gorgeous new 4K resoration of Jacques Demy’s The Umbrellas of Cherbourg. Assuming that as a fan of La La Land, you are not afraid of or intimidated by musicals, you have the chance to see how much Chazelle was influenced by this 60’s French classic, even if he balked at the sheer amount of singing and split the difference with American MGM musicals of the 40’s and 50’s.

To Chazelle’s credit, he is another definite cinephile and made sure to make clear the inspiration that Demy’s film had on his own work, but it is always something I’ve found interesting to track myself, comparing two films from vastly different eras of cinema, and how one artist influenced another.

Purely on the surface level, there is the obvious comparisons, a love story between attractive actors, fueled by music and each character’s passions. While Sebastian (Ryan Gosling) and Mia (Emma Stone) are able to focus solely on their careers – jazz music and acting, respectively – Geneviève (Catherine Deneuve), and Guy (Nino Castelnuovo) have their love story greatly affected by his required military service. Sebastian and Mia start off as enemies, in traffic and as passing souls at Sebastian’s crushing restaurant job, as Geneviève and Guy begin their story already deeply in love, despite opposition from Geneviève’s mother and Guy’s own familial restraints, in the form of his sick aunt.

The colors in the film are another easy signifier, with Demy having the upper hand in the emergence of technicolor and designing the film to make full use of the range of colors provided by that film stock. Whether it’s Geneviève’s umbrella shop, or Guy’s auto repair shop (and enviable sweater game), Umbrellas is overflowing with color that’s directly in-step with the emotion that each character wears on their sleeve, and even more directly stated through their constant singing. There are no spoken lines of dialogue in Umbrellas, every line is sung through Michel Legrand’s all-timer of a score.

While modern film doesn’t have quite the same pop as original technicolor (the film vs digital debate should end when looking at the visuals of a film from the 60’s compared to a digital film shot five years ago) Chazelle is just as selective with his use of color, looking to Mia’s yellow dress, visible in the film’s poster and during her first dance with Sebastian, and while Sebastian’s wardrobe remains more earth-toned and neutral, unless he’s being embarrassed (Mia’s request for “I Ran” at the party where they re-connect), it’s the lighting in spaces where he plays his music, where he is in his element, that displays his inner joy and peace at working towards his dream.

Looking more directly at the plot, with spoilers ahead, the ending is where the comparison seems the most apt. In La La Land, Mia and Sebastian go their separate ways, until Mia happens upon Sebastian’s club, the one he dreamt of building throughout the film, with her husband. As Sebastian plays, we see how their story could have ended, with them together, starting a family of their own, with each character sharing a melancholic smile as they see one another across the room.

In Umbrellas, Guy and Geneviève are given the opportunity of closure that was only imagined for Mia and Sebastian, as Geneviève marries a jeweler, having become pregnant with Guy’s child. She leaves Cherbourg, only to happen upon the gas station he opened after marrying Madeline, the former nurse of his sickly aunt, now deceased. They share a conversation, reconnecting, and allowing the other to move on with their lives. Having both found families and success in their own ways, it is a decidedly downbeat ending, following the incredibly romantic story that preceded it, without ever losing the empathy and humanity that Demy allows each character.

It’s indicative of each filmmaker’s style, Chazelle’s dreamy “what-if” clashing with Demy’s more realistic “now what”. There’s more reality within Demy’s film, despite the constant singing and sense of color and tone that seems to elevate it above typical realism within film, while Chazelle seems to explore the quick rise to success that he experienced after Whiplash in 2014.

This is one of the main ideas that always makes me explore film history deeper, seeing how contemporary filmmakers that I enjoy have been influenced by films of the past, whether it’s looking at a similar narrative idea, the use of directing styles and visual ideas, or anything in between. This is all not to say that one film is better than another, or has more or less value, but that there is a deep history in this young medium, and you can begin to recognize where these artists came from, and where they may go next.